In this article we’ll explore how Apache Cassandra, the world’s most popular wide column store and 8th most popular database overall, will only grow as a cornerstone technology in a microservices platform. With a little theory to microservices, to some examples of microservices and underlying required infrastructure, we’ll show that any solution both capable of scaling and dealing with time-series data-models is going to need to depend upon Apache Cassandra as a persistence layer, despite having a polyglot persistence model at large.

microservices

Microservices is a term that’s come out of ThoughtWorks’ Martin Fowler and James Lewis. It’s a bit of a buzzword, basically a fresh revival of the parts of service orientated architecture that you should be focusing on and getting right. A lot of it hopefully is obvious to you already. If you’ve been doing service orientated architecture or even generally just unix programming properly over the years it might well be frustrating just how buzz “microservices” has become. But it’s worth keeping in mind how much garbage we’ve collected and how many aspects of service orientated architecture that we’ve gotten badly wrong over the years. Younger programmers certainly deserve the clarity that ThoughtWorks is giving us here.

Microservices, following the tips and guidelines from Sam Newman, can basically be broken down into four groups.

interfaces

Ensure that you standardise the systems architecture at large and especially the gaps or what we know as the APIs between services. Standardise upon practices and protocols that minimise coupling. Move from tightly coupled systems with many compile time dependencies and distributed published client libraries, to clearly defined and isolated runtime APIs. Take advantage of REST, especially level 3 in richardson’s maturity model, for the synchronous domain driven designed parts of your system. When it comes to event driven design use producer defined schemas, like that offered by Apache Thrift’s IDL which gives you embedded schemas for good forward and backward compatibility along with isolated APIs that prevent transitive dependencies creeping through your platform. Getting this right also means that within services teams get a lot more freedom and autonomy to implement as they like, which in turns diminishes the effects of Brook’s law.

deployment

Simplify deployment down to having just one way of deploying artifacts, of any type, to any environment. The process of deployment needs to be so easy that deploying continuously each and every change into production becomes standard practice. This often also requires some organisational and practical changes like moving to stable master codebases and getting developers comfortable with working with branches and dark launching.

monitoring

It isn’t just about the motto of “monitor everything” and to have all metrics and logs accessible in one central place, but to include synthetic requests to provide monitoring alerts that catch critical errors immediately, and to use correlation IDs to be able to easily put all the moving parts together for any one specific request.

architectural safety

Addressing the fallacies of distributed computing, ensure that services are as available as possible and consumers handle failures gracefully by using such mechanisms as circuit breakers, load balancing, and bulkheads.

If you want more than I can only highly recommend Sam Newman’s just published book on Building Microservices.

In this article, and when talking about microservices, i’m most interested in how Cassandra, one of the most popular databases in our industry and the database most realistic to the practical realities of distributed computing, comes into its own. Here Cassandra is relevant to the monitoring and architectural safety aspects of microservices, from looking at how monitoring is typically time series data, a known strength for Cassandra, and looking into how modern distributed systems should be put together.

Having worked in the enterprise for over a decade it’s clear that the relational database is at juxtaposition to the rest of our industry. The way we code against the RDMS, layer domain logic upon it, and at various layers up through the stack add additional complexity and cyclic dependencies with caches that require invalidation, makes it all too obvious we’ve been doing things wrong. You can see it in plain sight when watching presentations where people show their wonderful service orientated architectures or microservices platforms, and despite talking about how their services scale, are fault-tolerant and resilent, maybe even throwing in some fancy messaging system, there is still in the corner of their diagrams the magic unicorn – the relational database. Amidst all the promotion and praise for BASE architectures, the acceptance that our own services and those infrastructural like Solr, Elastic Search, or Kafka, need to work with eventual consistency so to achieve performance and availability, the relational database somehow gets a free ride, an exception, to all this common sense.

Martin Kleppman presented at Strange Loop last year and afterwards wrote an article “Turning the database inside out with Apache Sanza” that properly hits the nail on the head, perfectly describing my own woes around why the relational database has ruined back-end programming for us. And he sums it up rather elegantly to that the replication mechanism to databases needs to come out and become its own integral and accepted component to our systems designs. And this externalised replication is what we call streams and event driven design, and it leads us to de-normalised datasets and more time-series data models.

product examples

Let’s look at a few examples from FINN.no and see how these things work in practice.

First of all we know that Cassandra has a number of known strengths over other databases, from dealing with large volumes of data and providing superior performance on both write and read performance, to time series data and time-to-live data.

But one of the areas that’s not highlighted enough is that Cassandra’s CQL schema often provides a simpler schema over the SQL equivalent, something that’s easier to work with and for programmers today something that uses more natural types and fluent APIs.

After all the whole point with your microservices platform is that you’re writing smaller and smaller services, and those smaller services each come with their own private data models. As services and their schemas get smaller and simpler we find that we don’t need relationships and constraints and all the other complexities that the RDMS has to offer. Rather the constructs available to us in CQL are superior, and faster.

The first example is how we store the users search history. This shouldn’t be a product that needs to be explained to anyone. The CQL schema to this is incredibly simple and it takes advantage of the combination between partition and clustering keys. And it operates fast, just make sure to apply the “CLUSTERING ORDER BY” or you’ll be falling into a Cassandra anti-pattern where you’ll be left reading tons of tombstones each read.

CREATE TABLE users_search_history (

user_id text,

search_id timeuuid,

search_url text,

description text,

PRIMARY KEY (user_id, search_id)

)

WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (search_id desc);Another example is fraud detection, and while fraud detection is typically a complicated bounded context at large, breaking it down you may find individual components using small simple isolated schemas. Here we have a CQL schema, much simpler than its relational SQL schema counterpart not only because is it time-series using the clustering key, but using Cassandra’s collection type to store the scores of each of the rules calculated during the fraud detection’s expert rules system.

CREATE TABLE ad_scores (

adid bigint,

updated timeuuid,

rules map<text, int>,

PRIMARY KEY (adid, updated)

)So it shouldn’t be of any surprise that Cassandra is going to hit the sweet spot for particular services in a number of different ways in any polyglot persistence platform. But bring it back to the bigger picture and we can look at how we can remove that magic unicorn we keep seeing in systems designs’ overviews.

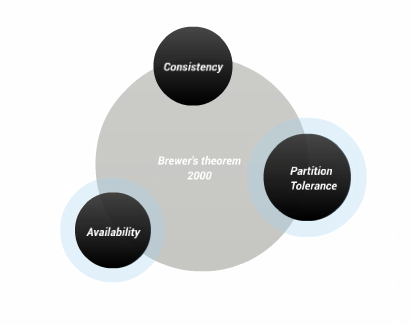

brewer’s theorem

Looking at the CAP theorem you recognise that to build a BASE microservices platform it means building AP systems. When you look at Martin Kleppman’s message that the replication is its own concern in your BASE platform, when you look at domain driven design and how to focus keeping your services within clear bounded contexts and then taking it further to use event driven design to further break those bounded contexts apart, you see that it ties back to the CAP theorem and it is for the sake of scalability and performance and even just simplicity in design, a preference for availability over consistency. Looking into it deeper in how streaming solutions often still need to write to raw event stores, and similar to a event sourcing model when a service needs to bootstrap its de-normalised dataset from scratch from data beyond that to which is stored in the stream’s history, you can see there is a parallel to partition tolerance and how it, just like partition tolerance within the CAP theorem, is a hard fast requirement to any distributed architecture.

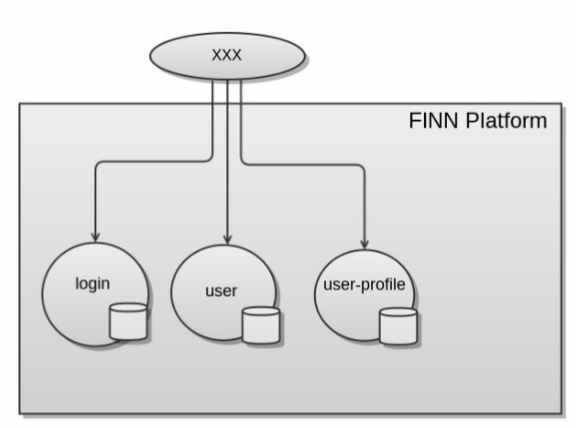

Here’s a simple example of a web application (named “xxx”) making three synchronous requests to underlying services in our platform when the user logs in. One service call to do the authentication, and the other two to fetch user data due to that user data being stored/available in different back-end systems.

It’s not difficult to see this isn’t a great design. First of all it’s keeping all the logic on how these services calls are initiated and how the data joined together high up in the presentation layer. It’s also not a great performer unless you’re willing to introduce concurrency code up in your presentation layer.

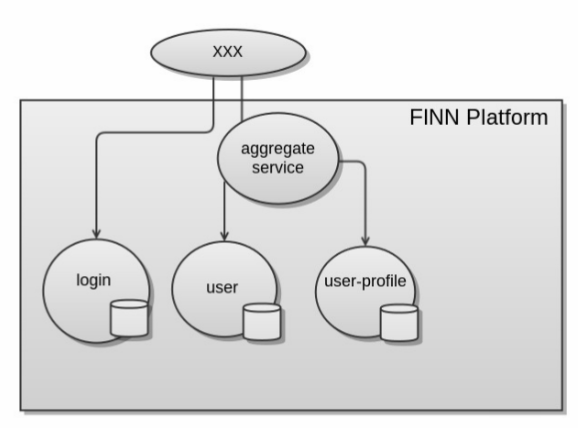

The obvious thing to do is introduce an aggregate service so that the web app only needs to make two inner requests and much of the logic, including any concurrency code, is pushed down into the platform and into the bounded context where it belongs. Another thing that typically happens here is that a cache, one that requires invalidation, is added into the aggregate service to address performance and availability.

But it’s a hack. Now you have more network traffic than before and more overall complexity, and just a poor and possibly very slow system of eventual consistency.

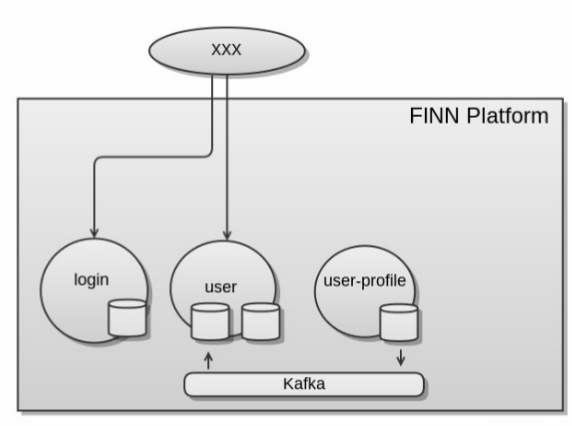

There is a better way, imagine there was but one service and all the data in a shared schema and then bring the replication mechanism of the database out into a stream to realise this. That is de-normalise the data from the auxiliary user-profile service back into the original user service. What you end up with is faster, more available, better scaling solution. Once you’re in the swing of event driven design and de-normalised datasets this is simpler solution too.

infrastructure examples

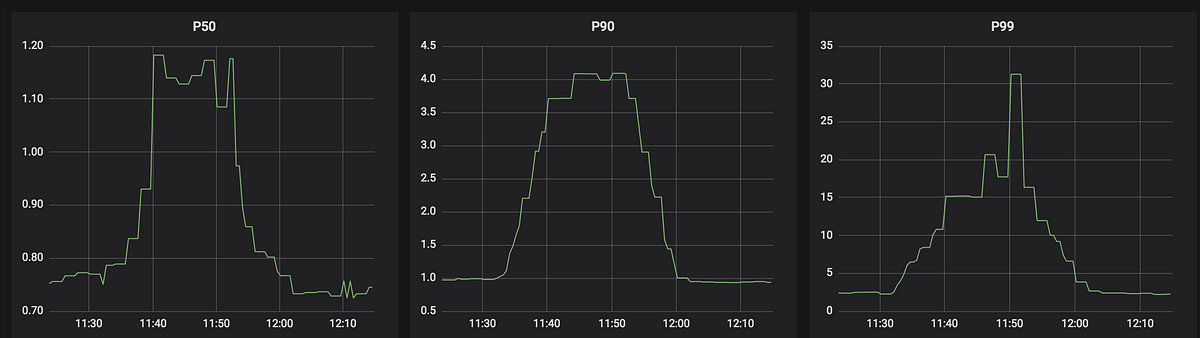

With some ideas of how Cassandra can become important for a successful microservices platform within product development let’s look into how Cassandra fits into the infastructure and operations side of things. A trap i suspect a lot of people are getting themselves into when starting off with microservices is that they haven’t got the infrastructure required in place first. Even if James Lewis and Sam Newman puts extra emphasis on the needs for deployment and monitoring tools it still can be all too easily overlooked just how demanding this really is. It’s not just about monitoring and logging everything and then making it available in a centralised place. It’s not just about having reproducible containers on an elastic platform, but about all the infrastructure tools and services being rock stable and equally elastic. You don’t want to be running a microservices platform and have crucial monitoring and logging tools fail on you, particularly in any crisis or in the middle of any critical operation.

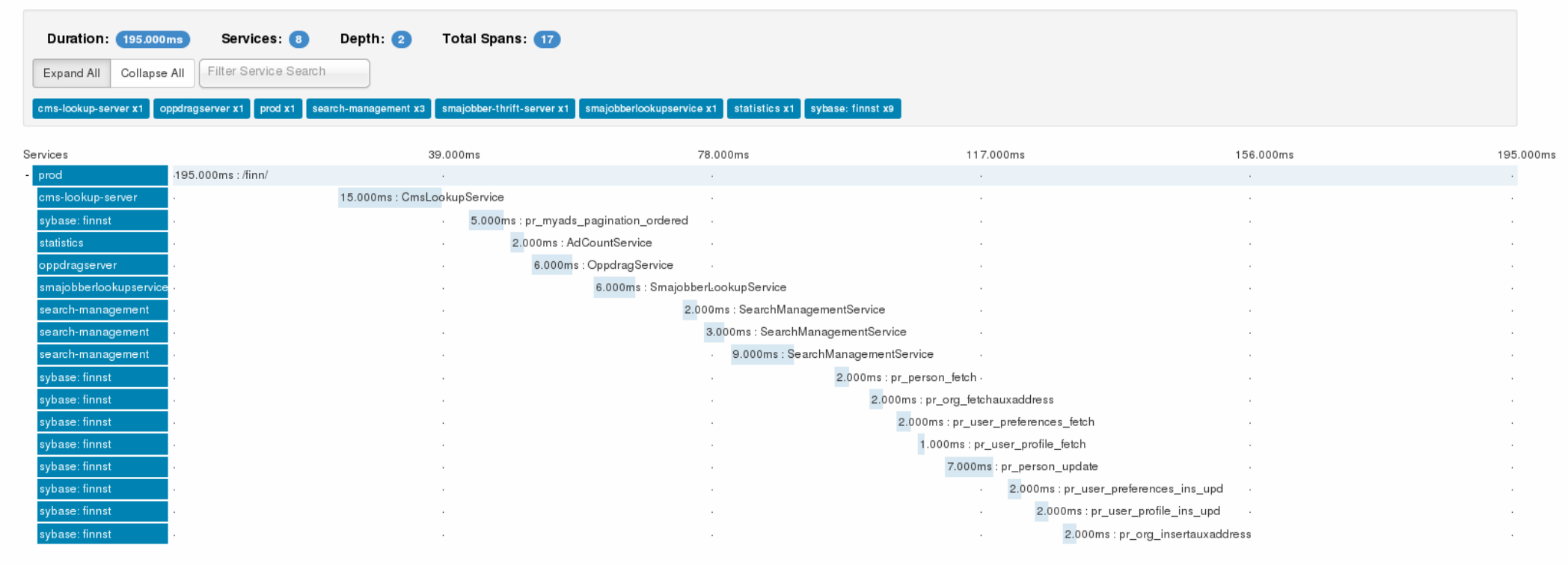

When it comes to correlation IDs a brilliant tool out there is Zipkin from Twitter. Zipkin provides for you in all your applications and services this correlation ID, a unique ID for each user request, which you can for example put into your log4j thread context or MDC and then via a tool like Kibana be able to put together all the logs from across your whole platform for one specific user request. But Zipkin goes a lot further than this, based off Google’s Dapper paper, it provides for you distributed tracing or profiling of these individual requests.

Naturally Zipkin can be put together with Cassandra, the best fit as it’s perfect for large volumes of time series data. We also use scribe for the sending of the trace messages from all the jvms throughout our platform over to the zipkin collector which then stores them into Cassandra.

Below is the typical page in Zipkin. Under the list of services the first row is the user’s request, here we can see that it took 195ms. Then under that we can see when and how long all the individual service calls took place. We can see which back-end services are running properly in parallel and which service calls are sequential. Services like Solr, Elastic Search, the Kafka producers, and of course Cassandra, are all listed as well. Not only is this fantastic for keeping your platform tuned for performance but it’s a great tool for helping to figure out what’s going on with those slow requests you’ve got, for example in the top 5th percentile.

It’s also a great tool to help keep teams up to date with all the constantly evolving moving parts that exist in a microservices platform, something that’ll no doubt be outdated a week after any manual catalog documentation was written. This is especially useful for front end developers that usually haven’t the faintest idea what’s going on behind the scenes.

This visualisation can also be offered from within the browser, both Firefox and Chrome have plugins, so that developers can see what’s happening near real-time as they make requests.

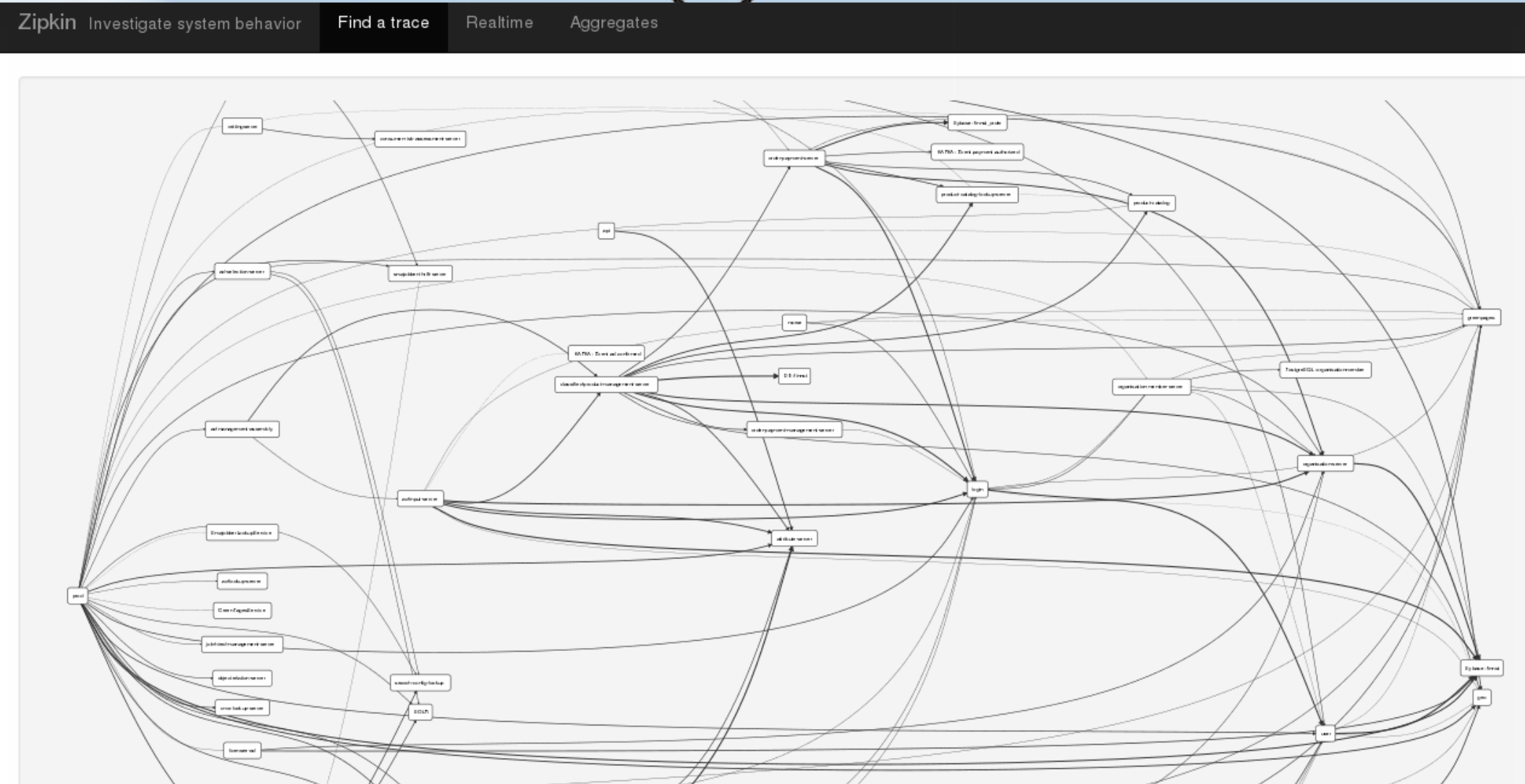

Something that we’re added to Zipkin is a cascasding job that runs nightly in our hadoop yarn cluster, that aggregates all the different traces made during the day and builds up a graph of the platform showing which services are calling services. In this graph on the left hand side you will see our web and batch applications, then to the right of that the microservices moving down the stack the further to the right you go. Legacy databases with shared schemas end up as big honey pots on the very right while databases with properly isolated schemas appear as satellites to the services that own them. If you’re undertaking a move towards event driven design then you’ll see the connections between services and especially across bounded contexts break apart, and you should see those bounded contexts become more grouped neighbourhoods for themselves.

This cascading job that aggregates this data should now be available in the original Twitter Github repository, otherwise you’ll find it in FINN’s fork of it.

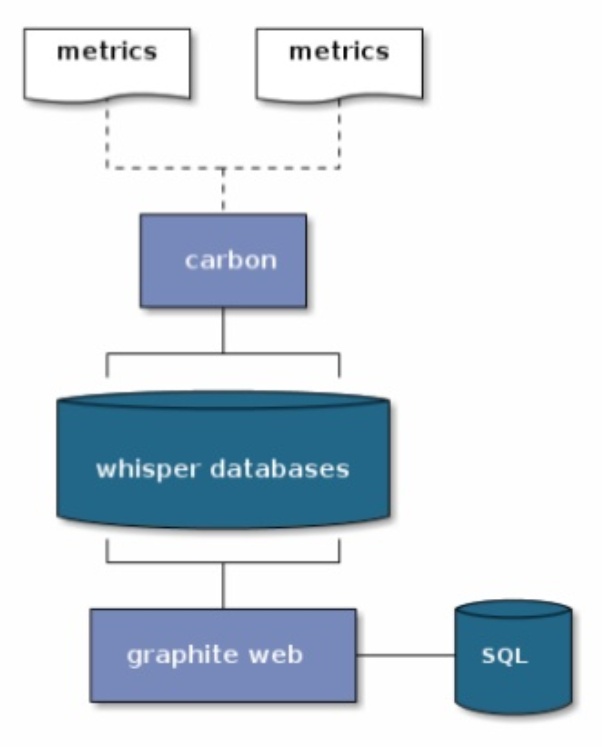

Another crucial infrastructure tool is Grafana, and the Graphite and StatsD stack underneath it. Grafana and Graphite is one of those must-have tools in your infrastructure, but the problem is it just doesn’t scale. Indeed the carbon and whisper components to graphite are dead in the water. We’ve hit this problem and looked into the alternatives, and there’s one interesting alternative out there based on Cassandra, which only makes sense as it’s another perfect match for time series data.

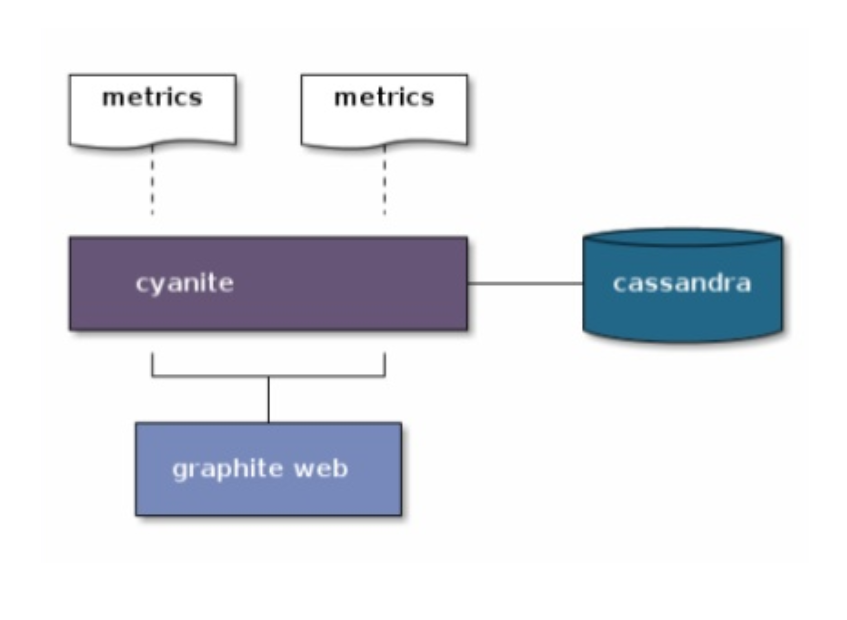

The plugin to Graphite is called Cyanite and very simply replaces all the carbon and whisper components. In an earlier version it was quite limited and you couldn’t for example get wildcarded paths in graphite working, but it now bundles with Elastic Search to give you a fully functional Graphite.

If you want to take a go at setting this up and see for yourself just how easy it is to get running, and how easily Grafana, Graphite, Cyanite, Elastic Search, and Cassandra, are configured together take a look at the GitHub repository docker-cyanite-grafana. It’s a docker image – just run build.sh and once everything has started up run test.sh to start feeding in dummy metrics and test away all the grafana features you’re used to working with.

a compliment to the modern enterprise platform

With this run through of just a few product and infrastructure examples it’s quickly obvious how useful Cassandra is to have established in any polyglot persistence model. And with an understanding on distributed computing it becomes even harder to deny Cassandra its natural home in the modern enterprise platform.

Tags:MicroservicesCassandraRESTThriftKafka