Performance of a database system depends on many factors: hardware, configuration, database schema, amount of data, workload type, network latency, and many others. Therefore, one typically can’t tell the actual performance of such system without first measuring it. In this blog post I’m describing how to build a benchmarking tool for Apache Cassandra from scratch in Rust and how to avoid many pitfalls. The techniques I show are applicable to any system with an async API.

Apache Cassandra is a popular, scalable, distributed, open-source database system.

It comes with its own benchmarking tool cassandra-stress that can issue queries in parallel and measure

throughtput and response times. It offers not just a few built-in standard benchmarks, but also allows defining

custom schemas and workloads, making it really versatile. So why write another one?

Being written in Java, cassanda-stress has a few downsides:

-

It consumes a significant amount of CPU and RAM resources by itself. This makes it a bad idea to run it on the same machine as the database server, because the amount of resources available to the server would be strongly reduced. This problem obviously exists for just any benchmarking tool regardless of its performance, but I was really surprised to find that

cassandra-stressoften takes about the same amount of CPU time as the server it benchmarks, essentially halving the CPU time available to Cassandra. This also means that even when running it on a separate computer, you need to make sure it is as powerful as the system under test. Or in case of bigger clusters - you need a decent cluster just for the client machines. -

It requires warmup for the JVM. This is a problem of all JVM-based benchmarking tools (including excellent benchmarking frameworks like JMH). You can’t run a test for a second or even a few secods, because initial measurements are inaccurate and need to be thrown-away. This problem might be considered a minor annoyance, but it seriously gets in a way if you ever wanted to measure the effect of JVM warmup on the server side performance (which happens e.g. after restarting the server). In this case you can’t tell the effects of the warmup on the server side from the effects on the client side.

-

JVM that runs the benchmark tool and its GC are an additional source of unpredictable delays. The reported latency analysis is affected by the delays happening on the client, so these ideally should be as low as possible. Modern Java GCs claim sub-10 ms pause times, and I find them too high for benchmarking a system that aims for sub millisecond average response-times.

A natively compiled, GC-less language like C, C++ or Rust addresses all of these issues. Let’s see how we can write a benchmarking tool in Rust.

Before we can issue any queries, we need to establish a connection to the database and obtain a session. To access Cassandra, we’ll use cassandra_cpp crate which is a Rust wrapper over the official Cassandra driver for C++ from DataStax. There exist other third-party drivers developed natively in Rust from scratch, but at the time of writing this post, they weren’t production ready.

Installing the driver on Ubuntu is straightforward:

sudo apt install libuv1 libuv1-dev sudo dpkg -i cassandra-cpp-driver_2.15.3-1_amd64.deb sudo dpkg -i cassandra-cpp-driver-dev_2.15.3-1_amd64.deb

Then we need to add cassandra_cpp dependency to Cargo.toml:

cassandra-cpp = "0.15.1"

Configuring the connection is performed through Cluster type:

use cassandra_cpp::*;

let mut cluster = Cluster::default();

cluster.set_contact_points("localhost").unwrap();

cluster.set_core_connections_per_host(1).unwrap();

cluster.set_max_connections_per_host(1).unwrap();

cluster.set_queue_size_io(1024).unwrap();

cluster.set_num_threads_io(4).unwrap();

cluster.set_connect_timeout(time::Duration::seconds(5));

cluster.set_load_balance_round_robin();

Finally, we can connect:

let session = match cluster.connect() {

Ok(s) => s,

Err(e) => {

eprintln!("error: Failed to connect to Cassandra: {}", e);

exit(1)

}

}

Now that we have the session, we can issue queries.

How hard could writing a database benchmark be? It is just sending queries in a loop and measuring how long they take, isn’t it?

For simplicity, let’s assume there already exists a table test in keyspace1 with the following schema:

CREATE TABLE keyspace1.test(pk BIGINT PRIMARY KEY, col BIGINT);

Let’s issue some reads from this table and measure how long they took:

use std::time::{Duration, Instant};

let session = // ... setup the session

let count = 100000;

let start = Instant::now();

for i in 0..count {

session

.execute(&stmt!("SELECT * FROM keyspace1.test WHERE pk = 1"))

.wait()

.unwrap();

}

let end = Instant::now();

println!(

"Throughput: {:.1} request/s",

1000000.0 * count as f64 / (end - start).as_micros() as f64

);

I bet you’ve seen similar benchmarking code in some benchmarks on the Internet. I’ve seen results from code like this being used to justify a choice of one database system over another. Unfortunately, this simple code has a few very serious issues and can lead to incorrect conclusions about performance of the system:

-

The loop performs only one request at a time. In case of systems like Apache Cassandra which are optimised to handle many thousands of parallel requests, this leaves most of the available computing resources idle. Most (all?) modern CPUs have multiple cores. Hard drives also benefit from parallel access. Additionally, there is non-zero network latency for sending the request to the server and sending the response back to the client. Even if running this client code on the same computer, there is non-zero time needed for the operating system to deliver the data from one process to another over the loopback. During that time, the server has literally nothing to do. The result throughput you’ll get from such a naive benchmark loop will be significantly lower than the server is really capable of.

-

Sending a single query at a time precludes the driver from automatically batching multiple requests. Batching can improve the network bandwidth by using a more efficient data representation and can reduce the number of syscalls, e.g. by writing many requests to the network socket at once. Reading requests from the socket on the server side is also much more efficient if there are many available in the socket buffer.

-

The code doesn’t use prepared statements. Many database systems, not only Cassandra, but also many traditional relational database systems, have this feature for a reason: parsing and planning a query can be a substantial amount of work, and it is makes sense to do it only once.

-

The code is reading the same row over and over again. Depending on what you wish to measure this could be a good or a bad thing. In this case, the database system would cache the data fully and serve it from RAM, so you might actually overestimate the performance, because real workloads rarely fetch a single row in a loop. On the other hand, such test would make some sense if you deliberately want to test the happy-path performance of the cache layer.

As a result, the reported throughput is abysmally poor:

Throughput: 2279.7 request/s

The problems #3 and #4 are the easiest to solve. Let’s change the code to use a prepared statement, and let’s introduce a parameter so we’re not fetching the same row all the time:

use cassandra_cpp::*;

use std::time::{Duration, Instant};

let session = // ... setup the session

let statement = session

.prepare("SELECT * FROM keyspace1.test WHERE pk = ?")?

.wait()?;

let count = 100000;

let start = Instant::now();

for i in 0..count {

let mut statement = statement.bind();

statement.bind(0, i as i64)?;

session.execute(&statement).wait().unwrap();

}

let end = Instant::now();

println!(

"Throughput: {:.1} request/s",

1000000.0 * count as f64 / (end - start).as_micros() as f64

);

Unfortunately, the performance is still extremely low.

Throughput: 2335.9 request/s

To fix the problems #1 and #2, we need to send more than one query at a time.

In the codes above we’re calling wait() on the futures returned from the driver

and that call is blocking. And because our program is single-threaded, it can’t do anything

else while being blocked.

There are two approaches we can take:

-

Launch many threads and let each thread run its own loop coded in the way as shown above. I tried this, and you have to believe this approach requires hundreds of threads to get a decent performance from a single-node Cassandra cluster. I won’t show it here, because I don’t prefer this solution – it feels unnatural when the driver offers excellent async capabilities (but feel free to drop a comment and share your experience if you coded it by yourself). More importantly, this approach is susceptible to coordinated omission, where a single slow requests (e.g. blocked by server-side GC) could delay sending a bunch of other requests, hence making the reported response times too optimistic.

-

Use async programming model: don’t block immediately on the returned future after spawning a single request, but spawn many requests and collect results asynchronously when they are ready. This way we’re making sending requests independent from each other, thus avoiding coordinated omission. It is easy to do with

cassandra_cppand Cassandra C++ driver because internally it also uses that style. You can notice that almost all the functions of the driver return futures that are compatible with Rust’sasync/awaitfeature.

In order to be able to use async functions at all, first we need to initialize an async runtime.

I decided to use a very popular crate tokio. Installation is adding just the following line

to Cargo.toml:

tokio = { version = "0.2", features = ["full"] }

Now we can annotate the main function as async, replace wait with await, and call tokio::spawn

to launch the requests. Although await looks like blocking, it doesn’t block the calling thread, but

allows it to move on to the next task.

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> cassandra_cpp::Result<()> {

let mut cluster = Cluster::default();

// ... configure cluster

let session = cluster.connect_async().await?;

let statement = session

.prepare("SELECT * FROM keyspace1.test WHERE pk = ?")?

.await?;

let count = 100000;

let start = Instant::now();

for i in 0..count {

let mut statement = statement.bind();

statement.bind(0, i as i64).unwrap();

tokio::spawn(async {

let result = session.execute(&statement);

result.await.unwrap();

});

}

let end = Instant::now();

println!(

"Throughput: {:.1} request/s",

1000000.0 * count as f64 / (end - start).as_micros() as f64

);

Ok(())

}

Unfortunately, this doesn’t compile, because our friend borrow-checker

correctly notices that the async code inside of the loop can live longer than the

main() function and its local variables such as i, session and statement:

error[E0373]: async block may outlive the current function, but it borrows `i`, which is owned by the current function

262 | tokio::spawn(async {

...

help: to force the async block to take ownership of `i` (and any other referenced variables), use the `move` keyword

error[E0373]: async block may outlive the current function, but it borrows `statement`, which is owned by the current function

help: to force the async block to take ownership of `statement` (and any other referenced variables), use the `move` keyword

error[E0373]: async block may outlive the current function, but it borrows `session`, which is owned by the current function

help: to force the async block to take ownership of `session` (and any other referenced variables), use the `move` keyword

The compiler advices us to use move to move these shared variables into the async code:

// ...

for i in 0..count {

tokio::spawn(async move {

//...

Fortunately, the problem with the loop counter i and statement is gone now.

But that still doesn’t work for session:

error[E0382]: use of moved value: `session`

--> src/main.rs:262:33

|

255 | let session = cluster.connect_async().await.unwrap();

| ------- move occurs because `session` has type `cassandra_cpp::Session`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

...

262 | tokio::spawn(async move {

| _________________________________^

263 | | let result = session.execute(&statement);

| | ------- use occurs due to use in generator

264 | | result.await.unwrap();

265 | | });

| |_________^ value moved here, in previous iteration of loop

This is quite obvious – we’re spawning more than one async task here, but because session is not copyable,

there can only exist one of each. Of course, we don’t want multiple sessions or statements here – we need a single one shared

among all the tasks. But how to pass only session by reference but still use move for passing the loop

counter i and statement?

Let’s take the reference to session before the loop – references are copyable:

// ...

let session = &session;

for i in 0..count {

// ...

tokio::spawn(async move {

// ...

But this brings us back to the first problem of insufficient lifetime, though:

error[E0597]: `session` does not live long enough

--> src/main.rs:262:19

|

262 | let session = &session;

| ^^^^^^^^ borrowed value does not live long enough

...

265 | tokio::spawn(async move {

| ______________________-

266 | | let result = session.execute(&statement);

267 | | result.await.unwrap();

268 | | });

| |_________- argument requires that `session` is borrowed for `'static`

...

276 | }

| - `session` dropped here while still borrowed

So it looks like we can’t pass the session by move, because we want sharing, but we also can’t pass it by reference because the session doesn’t live long enough.

In one of the earlier blog bosts I showed how this problem can be solved by using scoped threads. The concept of scope allows to force all background tasks to finish before the shared variables are dropped.

Unfortunately, I haven’t found anything like scopes inside of the tokio crate.

A search reveals a ticket, but it has been closed

and the conclusion is a bit disappointing:

As @Matthias247 pointed out, one should be able to establish scopes at any point. However, there is no way to enforce the scope without blocking the thread. The best we can do towards enforcing the scope is to panic when used “incorrectly”. This is the strategy @Matthias247 has taken in his PRs. However, dropping adhoc is currently a key async rust pattern. I think this prohibits pancing when dropping a scope that isn’t 100% complete. If we do this, using a scope within a select! would lead to panics. We are at an impasse. Maybe if AsyncDrop lands in Rust then we can investigate this again. Until then, we have no way forward, so I will close this. It is definitely an unfortunate outcome.

Of course, if you are fine with blocking the thread on scope exit, you can use the tokio_scoped crate.

The lifetime problem can be also solved with automatic reference counting.

Let’s wrap the session and statement in Arc. Arc will keep the shared session and statement

live as long as there exists at least one unfinished task:

// ...

let session = Arc::new(session);

for i in 0..count {

let mut statement = statement.bind();

statement.bind(0, i as i64).unwrap();

let session = session.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

// ...

This compiles fine and it wasn’t even that hard! Let’s run it:

thread 'tokio-runtime-worker' panicked at 'called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value:

Error(CassError(LIB_REQUEST_QUEUE_FULL, "The request queue has reached capacity"), State { next_error: None, backtrace: InternalBacktrace { backtrace: None } })', src/main.rs:271:26

note: run with `RUST_BACKTRACE=1` environment variable to display a backtrace

We submitted 100000 async queries all at once and the client driver’s queue can’t hold so many.

Let’s do a quick temporary workaround: lower the count to 1000.

The benchmark finishes fine now:

Throughput: 3095975.2 request/s

But is the result correct? Is Apache Cassandra really so fast? I’d really love to use a database that can do 3+ mln queries per second on a developer’s laptop, but unfortunately this isn’t the case. The benchmark is still incorrect. Now we don’t wait at all for the results to come back from the database. The benchmark submits the queries to the driver’s queue as fast as possible and then it immediately considers its job done. So we only measured how fast we can send the queries to the local driver’s queue (not even how fast we can push them to the database server).

Look at what we’re doing with the result of the query:

// ...

let result = session.execute(&statement);

result.await.unwrap();

});

The problem is: we’re doing nothing! After unwrapping, we’re just throwing the result away.

Although the await might look like we were waiting for the result from the server, note this is

all happening in the coroutine and the top-level code doesn’t wait for it.

Can we pass the results back from the nested tasks to the top level and wait for them at the end? Yes! Tokio provides its own, async implementation of a communication channel. Let’s setup a channel, plug its sending side to the coroutine and receive at the top-level at the end, but before computing the end time:

let start = Instant::now();

let (tx, mut rx) = tokio::sync::mpsc::unbounded_channel();

let session = Arc::new(session);

for i in 0..count {

let mut statement = statement.bind();

statement.bind(0, i as i64).unwrap();

let session = session.clone();

let tx = tx.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

let query_start = Instant::now();

let result = session.execute(&statement);

result.await.unwrap();

let query_end = Instant::now();

let duration_micros= (query_end - query_start).as_micros();

tx.send(duration_micros).unwrap();

});

}

// We need to drop the top-level tx we created at the beginning,

// so all txs are dropped when all queries finish.

// Otherwise the following read loop would wait for more data forever.

drop(tx);

let mut successful_count = 0;

while let Some(duration) = rx.next().await {

// Here we get a sequence of durations

// We could use it also to compute e.g. the mean duration or the histogram

successful_count += 1;

}

let end = Instant::now();

println!(

"Throughput: {:.1} request/s",

1000000.0 * successful_count as f64 / (end - start).as_micros() as f64

);

This prints a much more accurate number:

Throughput: 91734.7 request/s

Can we now increase the count back to 100,000? Not yet. Although we’re waiting at the end, the loop still spins like crazy submitting all the queries at once and overflowing the queues. We need to slow it down.

We don’t want to exceed the capacity of the internal queues of the driver.

Hence, we need to keep the number of submitted but unfinished queries limited.

This is a good task for a semaphore. A semaphore is a structure that allows at most

N parallel tasks. Tokio comes with a nice, asynchronous implementation of semaphore.

The Semaphore structure allows a limited number of permits. The function of obtaining

a permit is asynchronous, so it composes with the other elements we already use here.

We’ll obtain a permit before spawning a task, and drop the permit after receiving the

results.

// ...

let parallelism_limit = 1000;

let semaphore = Arc::new(Semaphore::new(parallelism_limit));

for i in 0..count {

// ...

let permit = semaphore.clone().acquire_owned().await;

tokio::spawn(async move {

// ... run the query and await the result

// Now drop the permit;

// Actually it is sufficient to reference the permit value

// anywhere inside the coroutine so it is moved here and it would be dropped

// automatically at the closing brace. But drop is more explicitly

// telling the intent.

drop(permit);

}

});

// ...

Because the permit is passed to the asynchronous code that may outlive the

scope of main, here again we need to use Arc. We also needed to use an owned permit,

rather than the standard one obtained by acquire().

An owned permit can be moved, a standard one cannot.

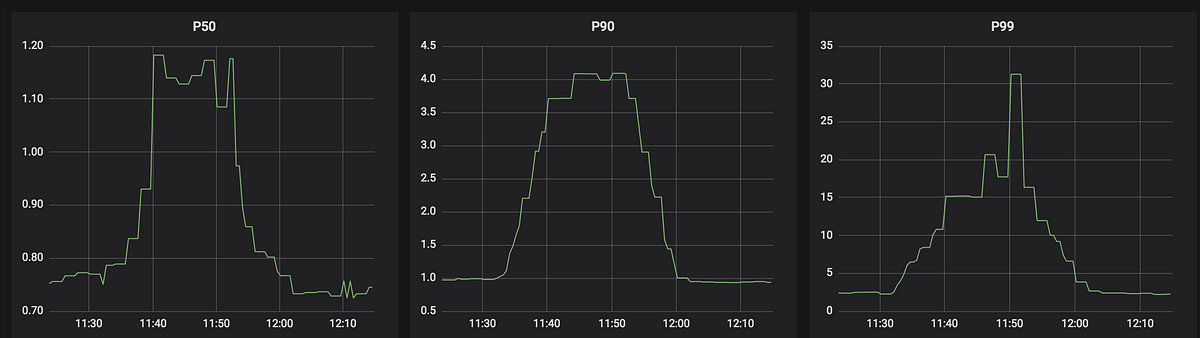

After putting it all together, and running the benchmark for a few times to warmup the server, the final throughput of running 100k queries was:

Throughput: 152374.3 request/s

Benchmarking is hard and it is easy to get incorrect results or arrive at incorrect conclusions.

Keep in mind that the way how you query data may severly affect the numbers you get. Watch for:

- Parallelism levels

- Number of connections / threads

- Coordinated omission

- Caching effects

- JVM warmup effects

- Data sizes (does the query even return any results?)

- Waiting for all the stuff to actually finish before reading the wall clock time

- Using the available database features (e.g. prepared statements)

- Queue size limits / backpressure

- CPU and other resources consumed by the benchmarking program

If you’d like to measure performance of your Cassandra cluster, you should try the tool I’m working on at the moment: Latte. Latte uses uses the approach described in this blog post to measure the throughput and response times. It is still very early-stage and I look forward to your feedback!